Note

Go to the end to download the full example code or to run this example in your browser via JupyterLite or Binder.

Combine predictors using stacking#

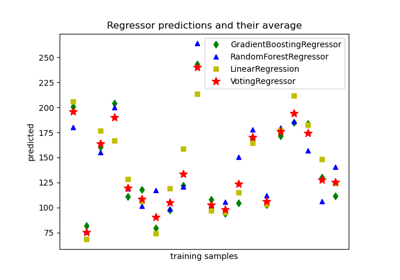

Stacking is an ensemble method. In this strategy, the

out-of-fold predictions from several base estimators are used to train a

meta-model that combines their outputs at inference time. Unlike

VotingRegressor, which averages predictions with

fixed (optionally user-specified) weights,

StackingRegressor learns the combination through its

final_estimator.

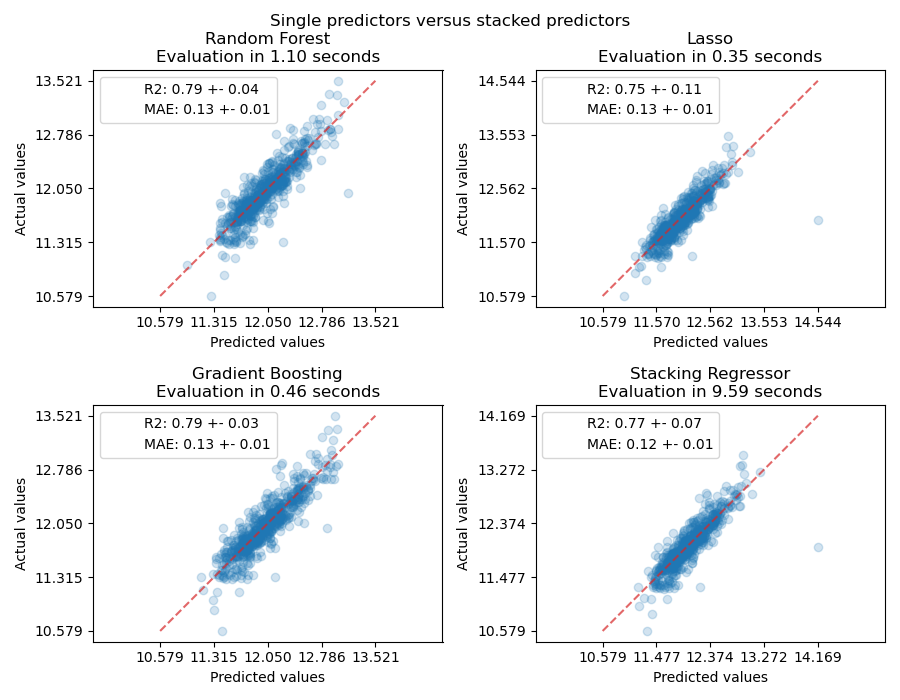

In this example, we illustrate the use case in which different regressors are stacked together and a final regularized linear regressor is used to output the prediction. We compare the performance of each individual regressor with the stacking strategy. Here, stacking slightly improves the overall performance.

# Authors: The scikit-learn developers

# SPDX-License-Identifier: BSD-3-Clause

Generate data#

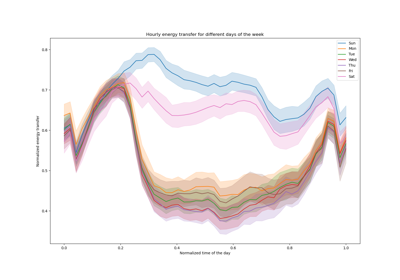

We use synthetic data generated from a sinusoid plus a linear trend with heteroscedastic Gaussian noise. A sudden drop is introduced, as it cannot be described by a linear model, but a tree-based model can naturally deal with it.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

rng = np.random.RandomState(42)

X = rng.uniform(-3, 3, size=500)

trend = 2.4 * X

seasonal = 3.1 * np.sin(3.2 * X)

drop = 10.0 * (X > 2).astype(float)

sigma = 0.75 + 0.75 * X**2

y = trend + seasonal - drop + rng.normal(loc=0.0, scale=np.sqrt(sigma))

df = pd.DataFrame({"X": X, "y": y})

_ = df.plot.scatter(x="X", y="y")

Stack of predictors on a single data set#

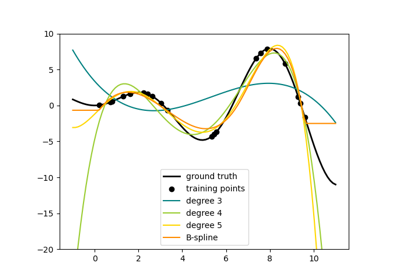

It is sometimes not evident which model is more suited for a given task, as

different model families can achieve similar performance while exhibiting

different strengths and weaknesses. Stacking combines their outputs to exploit

these complementary behaviors and can correct systematic errors that no single

model can fix on its own. With appropriate regularization in the

final_estimator, the StackingRegressor often

matches the strongest base model, and can outperform it when base learners’

errors are only partially correlated, allowing the combination to reduce

individual bias/variance.

Here, we combine 3 learners (linear and non-linear) and use the default

RidgeCV regressor to combine their outputs

together.

Note

Although some base learners include preprocessing (such as the

StandardScaler), the final_estimator does

not need additional preprocessing when using the default

passthrough=False, as it receives only the base learners’ predictions. If

passthrough=True, final_estimator should be a pipeline with proper

preprocessing.

from sklearn.ensemble import HistGradientBoostingRegressor, StackingRegressor

from sklearn.linear_model import RidgeCV

from sklearn.pipeline import make_pipeline

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures, SplineTransformer, StandardScaler

linear_ridge = make_pipeline(StandardScaler(), RidgeCV())

spline_ridge = make_pipeline(

SplineTransformer(n_knots=6, degree=3),

PolynomialFeatures(interaction_only=True),

RidgeCV(),

)

hgbt = HistGradientBoostingRegressor(random_state=0)

estimators = [

("Linear Ridge", linear_ridge),

("Spline Ridge", spline_ridge),

("HGBT", hgbt),

]

stacking_regressor = StackingRegressor(estimators=estimators, final_estimator=RidgeCV())

stacking_regressor

Measure and plot the results#

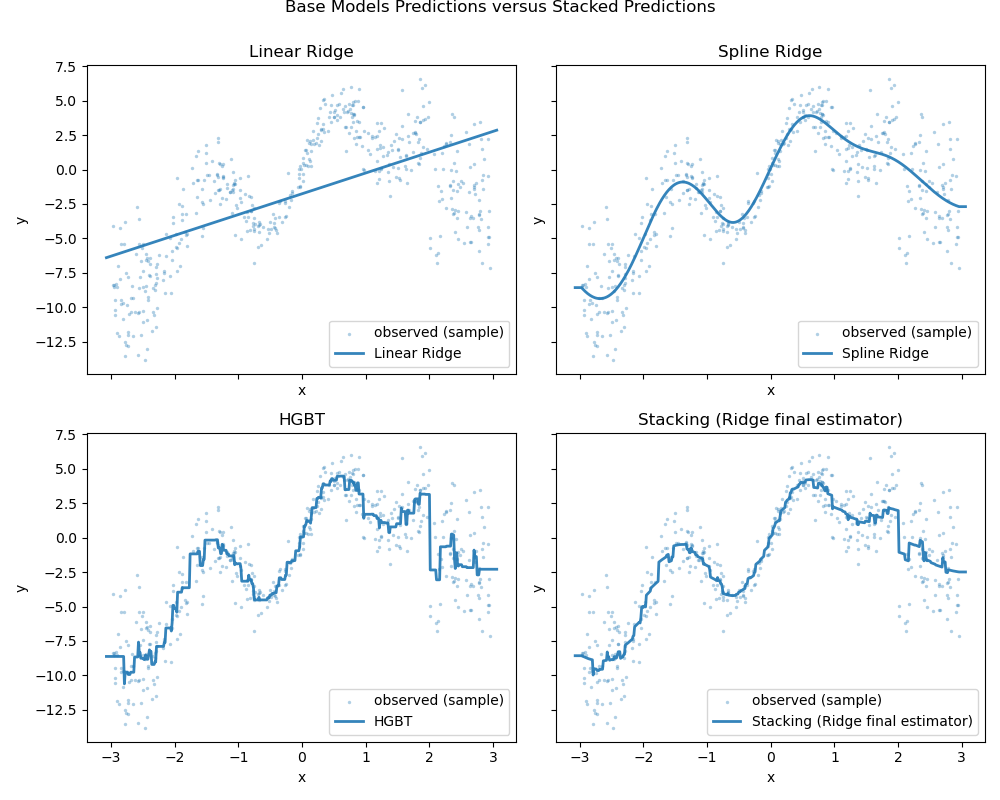

We can directly plot the predictions. Indeed, the sudden drop is correctly

described by the HistGradientBoostingRegressor

model (HGBT), but the spline model is smoother and less overfitting. The stacked

regressor then turns to be a smoother version of the HGBT.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

X = X.reshape(-1, 1)

linear_ridge.fit(X, y)

spline_ridge.fit(X, y)

hgbt.fit(X, y)

stacking_regressor.fit(X, y)

x_plot = np.linspace(X.min() - 0.1, X.max() + 0.1, 500).reshape(-1, 1)

preds = {

"Linear Ridge": linear_ridge.predict(x_plot),

"Spline Ridge": spline_ridge.predict(x_plot),

"HGBT": hgbt.predict(x_plot),

"Stacking (Ridge final estimator)": stacking_regressor.predict(x_plot),

}

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(10, 8), sharex=True, sharey=True)

axes = axes.ravel()

for ax, (name, y_pred) in zip(axes, preds.items()):

ax.scatter(

X[:, 0],

y,

s=6,

alpha=0.35,

linewidths=0,

label="observed (sample)",

)

ax.plot(x_plot.ravel(), y_pred, linewidth=2, alpha=0.9, label=name)

ax.set_title(name)

ax.set_xlabel("x")

ax.set_ylabel("y")

ax.legend(loc="lower right")

plt.suptitle("Base Models Predictions versus Stacked Predictions", y=1)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

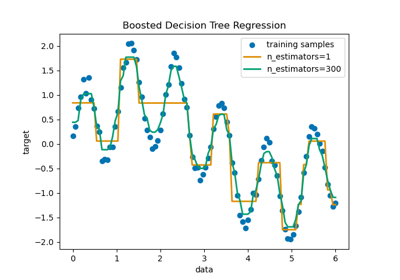

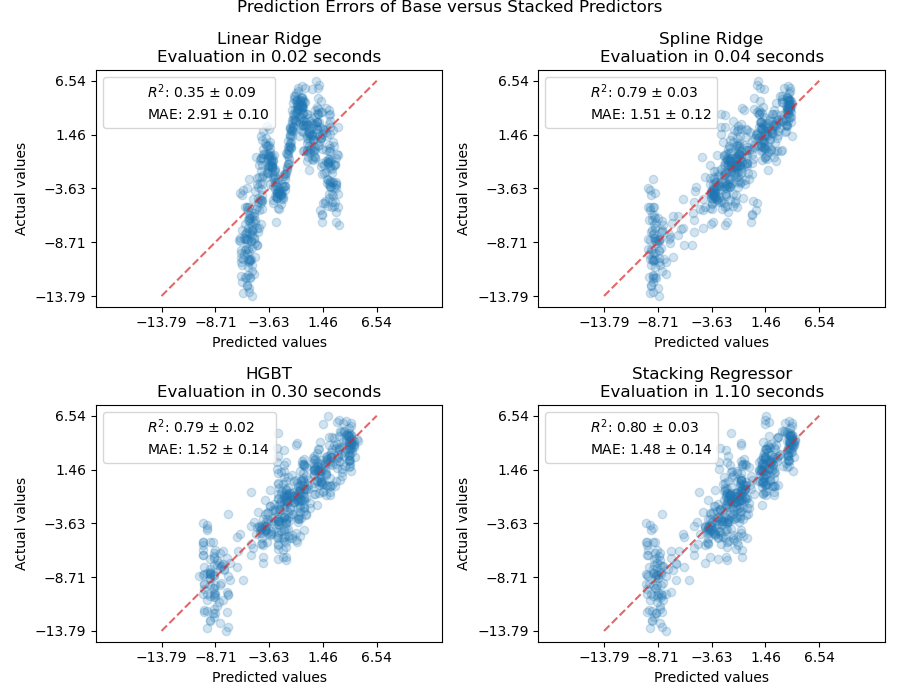

We can plot the prediction errors as well and evaluate the performance of the individual predictors and the stack of the regressors.

import time

from sklearn.metrics import PredictionErrorDisplay

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_predict, cross_validate

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(9, 7))

axs = np.ravel(axs)

for ax, (name, est) in zip(

axs, estimators + [("Stacking Regressor", stacking_regressor)]

):

scorers = {r"$R^2$": "r2", "MAE": "neg_mean_absolute_error"}

start_time = time.time()

scores = cross_validate(est, X, y, scoring=list(scorers.values()), n_jobs=-1)

elapsed_time = time.time() - start_time

y_pred = cross_val_predict(est, X, y, n_jobs=-1)

scores = {

key: (

f"{np.abs(np.mean(scores[f'test_{value}'])):.2f}"

r" $\pm$ "

f"{np.std(scores[f'test_{value}']):.2f}"

)

for key, value in scorers.items()

}

display = PredictionErrorDisplay.from_predictions(

y_true=y,

y_pred=y_pred,

kind="actual_vs_predicted",

ax=ax,

scatter_kwargs={"alpha": 0.2, "color": "tab:blue"},

line_kwargs={"color": "tab:red"},

)

ax.set_title(f"{name}\nEvaluation in {elapsed_time:.2f} seconds")

for name, score in scores.items():

ax.plot([], [], " ", label=f"{name}: {score}")

ax.legend(loc="upper left")

plt.suptitle("Prediction Errors of Base versus Stacked Predictors", y=1)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.subplots_adjust(top=0.9)

plt.show()

Even if the scores overlap considerably after cross-validation, the predictions from the stacked regressor are slightly better.

Once fitted, we can inspect the coefficients (or meta-weights) of the trained

final_estimator_ (as long as it is a linear model). They reveal how much the

individual estimators contribute to the the stacked regressor:

stacking_regressor.fit(X, y)

stacking_regressor.final_estimator_.coef_

array([-0.00446216, 0.44878552, 0.54762418])

We see that in this case, the HGBT model dominates, with the spline

ridge also contributing meaningfully. The plain linear model does not add

useful signal once those two are included; with

RidgeCV as the final_estimator, it is not

dropped, but receives a small negative weight to correct its residual bias.

If we use LassoCV as the

final_estimator, that small, unhelpful contribution is set exactly to zero,

yielding a simpler blend of the spline ridge and HGBT models.

from sklearn.linear_model import LassoCV

stacking_regressor = StackingRegressor(estimators=estimators, final_estimator=LassoCV())

stacking_regressor.fit(X, y)

stacking_regressor.final_estimator_.coef_

array([0. , 0.41148006, 0.56187293])

How to mimic SuperLearner with scikit-learn#

The SuperLearner [Polley2010] is a stacking strategy implemented as an R

package, but

not available off-the-shelf in Python. It is closely related to the

StackingRegressor, as both train the meta-model on

out-of-fold predictions from the base estimators.

The key difference is that SuperLearner estimates a convex set of

meta-weights (non-negative and summing to 1) and omits an intercept; by

contrast, StackingRegressor uses an unconstrained

meta-learner with an intercept by default (and can optionally include raw

features via passthrough).

Without an intercept, the meta-weights are directly interpretable as fractional contributions to the final prediction.

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

linear_reg = LinearRegression(fit_intercept=False, positive=True)

super_learner_like = StackingRegressor(

estimators=estimators, final_estimator=linear_reg

)

super_learner_like.fit(X, y)

super_learner_like.final_estimator_.coef_

array([2.41599724e-04, 4.48129539e-01, 5.49327451e-01])

The sum of meta-weights in the stacked regressor is close to 1.0, but not exactly one:

super_learner_like.final_estimator_.coef_.sum()

np.float64(0.9976985896404211)

Beyond interpretability, the normalization to 1.0 constraint in the SuperLearner

presents the following advantages:

Consensus-preserving: if all base models output the same value at a point, the ensemble returns that same value (no artificial amplification or attenuation).

Translation-equivariant: adding a constant to every base prediction shifts the ensemble by the same constant.

Removes one degree of freedom: avoiding redundancy with a constant term and modestly stabilizing weights under collinearity.

The cleanest way to enforce the coefficient normalization with scikit-learn is by defining a custom estimator, but doing so is beyond the scope of this tutorial.

Conclusions#

The stacked regressor combines the strengths of the different regressors. However, notice that training the stacked regressor is much more computationally expensive than selecting the best performing model.

References

Polley, E. C. and van der Laan, M. J., Super Learner In Prediction, 2010.

Total running time of the script: (0 minutes 5.844 seconds)

Related examples