Note

Click here to download the full example code or to run this example in your browser via Binder

Poisson regression and non-normal loss¶

This example illustrates the use of log-linear Poisson regression on the French Motor Third-Party Liability Claims dataset from 1 and compares it with a linear model fitted with the usual least squared error and a non-linear GBRT model fitted with the Poisson loss (and a log-link).

A few definitions:

A policy is a contract between an insurance company and an individual: the policyholder, that is, the vehicle driver in this case.

A claim is the request made by a policyholder to the insurer to compensate for a loss covered by the insurance.

The exposure is the duration of the insurance coverage of a given policy, in years.

The claim frequency is the number of claims divided by the exposure, typically measured in number of claims per year.

In this dataset, each sample corresponds to an insurance policy. Available features include driver age, vehicle age, vehicle power, etc.

Our goal is to predict the expected frequency of claims following car accidents for a new policyholder given the historical data over a population of policyholders.

- 1

A. Noll, R. Salzmann and M.V. Wuthrich, Case Study: French Motor Third-Party Liability Claims (November 8, 2018). doi:10.2139/ssrn.3164764

print(__doc__)

# Authors: Christian Lorentzen <lorentzen.ch@gmail.com>

# Roman Yurchak <rth.yurchak@gmail.com>

# Olivier Grisel <olivier.grisel@ensta.org>

# License: BSD 3 clause

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

The French Motor Third-Party Liability Claims dataset¶

Let’s load the motor claim dataset from OpenML: https://www.openml.org/d/41214

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml

df = fetch_openml(data_id=41214, as_frame=True).frame

df

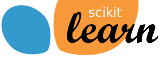

The number of claims (ClaimNb) is a positive integer that can be modeled

as a Poisson distribution. It is then assumed to be the number of discrete

events occurring with a constant rate in a given time interval (Exposure,

in units of years).

Here we want to model the frequency y = ClaimNb / Exposure conditionally

on X via a (scaled) Poisson distribution, and use Exposure as

sample_weight.

df["Frequency"] = df["ClaimNb"] / df["Exposure"]

print("Average Frequency = {}"

.format(np.average(df["Frequency"], weights=df["Exposure"])))

print("Fraction of exposure with zero claims = {0:.1%}"

.format(df.loc[df["ClaimNb"] == 0, "Exposure"].sum() /

df["Exposure"].sum()))

fig, (ax0, ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(ncols=3, figsize=(16, 4))

ax0.set_title("Number of claims")

_ = df["ClaimNb"].hist(bins=30, log=True, ax=ax0)

ax1.set_title("Exposure in years")

_ = df["Exposure"].hist(bins=30, log=True, ax=ax1)

ax2.set_title("Frequency (number of claims per year)")

_ = df["Frequency"].hist(bins=30, log=True, ax=ax2)

Out:

Average Frequency = 0.10070308464041304

Fraction of exposure with zero claims = 93.9%

The remaining columns can be used to predict the frequency of claim events. Those columns are very heterogeneous with a mix of categorical and numeric variables with different scales, possibly very unevenly distributed.

In order to fit linear models with those predictors it is therefore necessary to perform standard feature transformations as follows:

from sklearn.pipeline import make_pipeline

from sklearn.preprocessing import FunctionTransformer, OneHotEncoder

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler, KBinsDiscretizer

from sklearn.compose import ColumnTransformer

log_scale_transformer = make_pipeline(

FunctionTransformer(np.log, validate=False),

StandardScaler()

)

linear_model_preprocessor = ColumnTransformer(

[

("passthrough_numeric", "passthrough",

["BonusMalus"]),

("binned_numeric", KBinsDiscretizer(n_bins=10),

["VehAge", "DrivAge"]),

("log_scaled_numeric", log_scale_transformer,

["Density"]),

("onehot_categorical", OneHotEncoder(),

["VehBrand", "VehPower", "VehGas", "Region", "Area"]),

],

remainder="drop",

)

A constant prediction baseline¶

It is worth noting that more than 93% of policyholders have zero claims. If we were to convert this problem into a binary classification task, it would be significantly imbalanced, and even a simplistic model that would only predict mean can achieve an accuracy of 93%.

To evaluate the pertinence of the used metrics, we will consider as a baseline a “dummy” estimator that constantly predicts the mean frequency of the training sample.

from sklearn.dummy import DummyRegressor

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

df_train, df_test = train_test_split(df, test_size=0.33, random_state=0)

dummy = Pipeline([

("preprocessor", linear_model_preprocessor),

("regressor", DummyRegressor(strategy='mean')),

]).fit(df_train, df_train["Frequency"],

regressor__sample_weight=df_train["Exposure"])

Let’s compute the performance of this constant prediction baseline with 3 different regression metrics:

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

from sklearn.metrics import mean_absolute_error

from sklearn.metrics import mean_poisson_deviance

def score_estimator(estimator, df_test):

"""Score an estimator on the test set."""

y_pred = estimator.predict(df_test)

print("MSE: %.3f" %

mean_squared_error(df_test["Frequency"], y_pred,

sample_weight=df_test["Exposure"]))

print("MAE: %.3f" %

mean_absolute_error(df_test["Frequency"], y_pred,

sample_weight=df_test["Exposure"]))

# Ignore non-positive predictions, as they are invalid for

# the Poisson deviance.

mask = y_pred > 0

if (~mask).any():

n_masked, n_samples = (~mask).sum(), mask.shape[0]

print(f"WARNING: Estimator yields invalid, non-positive predictions "

f" for {n_masked} samples out of {n_samples}. These predictions "

f"are ignored when computing the Poisson deviance.")

print("mean Poisson deviance: %.3f" %

mean_poisson_deviance(df_test["Frequency"][mask],

y_pred[mask],

sample_weight=df_test["Exposure"][mask]))

print("Constant mean frequency evaluation:")

score_estimator(dummy, df_test)

Out:

Constant mean frequency evaluation:

MSE: 0.564

MAE: 0.189

mean Poisson deviance: 0.625

(Generalized) linear models¶

We start by modeling the target variable with the (l2 penalized) least

squares linear regression model, more comonly known as Ridge regression. We

use a low penalization alpha, as we expect such a linear model to under-fit

on such a large dataset.

The Poisson deviance cannot be computed on non-positive values predicted by

the model. For models that do return a few non-positive predictions (e.g.

Ridge) we ignore the corresponding samples,

meaning that the obtained Poisson deviance is approximate. An alternative

approach could be to use TransformedTargetRegressor

meta-estimator to map y_pred to a strictly positive domain.

print("Ridge evaluation:")

score_estimator(ridge_glm, df_test)

Out:

Ridge evaluation:

MSE: 0.560

MAE: 0.177

WARNING: Estimator yields invalid, non-positive predictions for 1315 samples out of 223745. These predictions are ignored when computing the Poisson deviance.

mean Poisson deviance: 0.601

Next we fit the Poisson regressor on the target variable. We set the

regularization strength alpha to approximately 1e-6 over number of

samples (i.e. 1e-12) in order to mimic the Ridge regressor whose L2 penalty

term scales differently with the number of samples.

Since the Poisson regressor internally models the log of the expected target value instead of the expected value directly (log vs identity link function), the relationship between X and y is not exactly linear anymore. Therefore the Poisson regressor is called a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) rather than a vanilla linear model as is the case for Ridge regression.

from sklearn.linear_model import PoissonRegressor

n_samples = df_train.shape[0]

poisson_glm = Pipeline([

("preprocessor", linear_model_preprocessor),

("regressor", PoissonRegressor(alpha=1e-12, max_iter=300))

])

poisson_glm.fit(df_train, df_train["Frequency"],

regressor__sample_weight=df_train["Exposure"])

print("PoissonRegressor evaluation:")

score_estimator(poisson_glm, df_test)

Out:

PoissonRegressor evaluation:

MSE: 0.560

MAE: 0.186

mean Poisson deviance: 0.594

Gradient Boosting Regression Trees for Poisson regression¶

Finally, we will consider a non-linear model, namely Gradient Boosting

Regression Trees. Tree-based models do not require the categorical data to be

one-hot encoded: instead, we can encode each category label with an arbitrary

integer using OrdinalEncoder. With this

encoding, the trees will treat the categorical features as ordered features,

which might not be always a desired behavior. However this effect is limited

for deep enough trees which are able to recover the categorical nature of the

features. The main advantage of the

OrdinalEncoder over the

OneHotEncoder is that it will make training

faster.

Gradient Boosting also gives the possibility to fit the trees with a Poisson loss (with an implicit log-link function) instead of the default least-squares loss. Here we only fit trees with the Poisson loss to keep this example concise.

from sklearn.experimental import enable_hist_gradient_boosting # noqa

from sklearn.ensemble import HistGradientBoostingRegressor

from sklearn.preprocessing import OrdinalEncoder

tree_preprocessor = ColumnTransformer(

[

("categorical", OrdinalEncoder(),

["VehBrand", "VehPower", "VehGas", "Region", "Area"]),

("numeric", "passthrough",

["VehAge", "DrivAge", "BonusMalus", "Density"]),

],

remainder="drop",

)

poisson_gbrt = Pipeline([

("preprocessor", tree_preprocessor),

("regressor", HistGradientBoostingRegressor(loss="poisson",

max_leaf_nodes=128)),

])

poisson_gbrt.fit(df_train, df_train["Frequency"],

regressor__sample_weight=df_train["Exposure"])

print("Poisson Gradient Boosted Trees evaluation:")

score_estimator(poisson_gbrt, df_test)

Out:

Poisson Gradient Boosted Trees evaluation:

MSE: 0.560

MAE: 0.184

mean Poisson deviance: 0.575

Like the Poisson GLM above, the gradient boosted trees model minimizes the Poisson deviance. However, because of a higher predictive power, it reaches lower values of Poisson deviance.

Evaluating models with a single train / test split is prone to random fluctuations. If computing resources allow, it should be verified that cross-validated performance metrics would lead to similar conclusions.

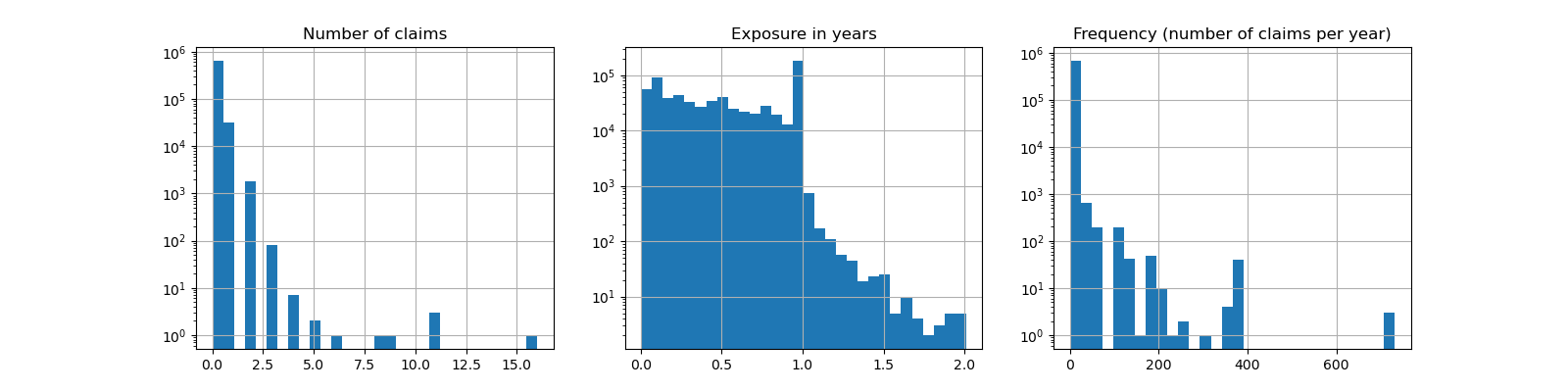

The qualitative difference between these models can also be visualized by comparing the histogram of observed target values with that of predicted values:

fig, axes = plt.subplots(nrows=2, ncols=4, figsize=(16, 6), sharey=True)

fig.subplots_adjust(bottom=0.2)

n_bins = 20

for row_idx, label, df in zip(range(2),

["train", "test"],

[df_train, df_test]):

df["Frequency"].hist(bins=np.linspace(-1, 30, n_bins),

ax=axes[row_idx, 0])

axes[row_idx, 0].set_title("Data")

axes[row_idx, 0].set_yscale('log')

axes[row_idx, 0].set_xlabel("y (observed Frequency)")

axes[row_idx, 0].set_ylim([1e1, 5e5])

axes[row_idx, 0].set_ylabel(label + " samples")

for idx, model in enumerate([ridge_glm, poisson_glm, poisson_gbrt]):

y_pred = model.predict(df)

pd.Series(y_pred).hist(bins=np.linspace(-1, 4, n_bins),

ax=axes[row_idx, idx+1])

axes[row_idx, idx + 1].set(

title=model[-1].__class__.__name__,

yscale='log',

xlabel="y_pred (predicted expected Frequency)"

)

plt.tight_layout()

The experimental data presents a long tail distribution for y. In all

models, we predict the expected frequency of a random variable, so we will

have necessarily fewer extreme values than for the observed realizations of

that random variable. This explains that the mode of the histograms of model

predictions doesn’t necessarily correspond to the smallest value.

Additionally, the normal distribution used in Ridge has a constant

variance, while for the Poisson distribution used in PoissonRegressor and

HistGradientBoostingRegressor, the variance is proportional to the

predicted expected value.

Thus, among the considered estimators, PoissonRegressor and

HistGradientBoostingRegressor are a-priori better suited for modeling the

long tail distribution of the non-negative data as compared to the Ridge

model which makes a wrong assumption on the distribution of the target

variable.

The HistGradientBoostingRegressor estimator has the most flexibility and

is able to predict higher expected values.

Note that we could have used the least squares loss for the

HistGradientBoostingRegressor model. This would wrongly assume a normal

distributed response variable as does the Ridge model, and possibly

also lead to slightly negative predictions. However the gradient boosted

trees would still perform relatively well and in particular better than

PoissonRegressor thanks to the flexibility of the trees combined with the

large number of training samples.

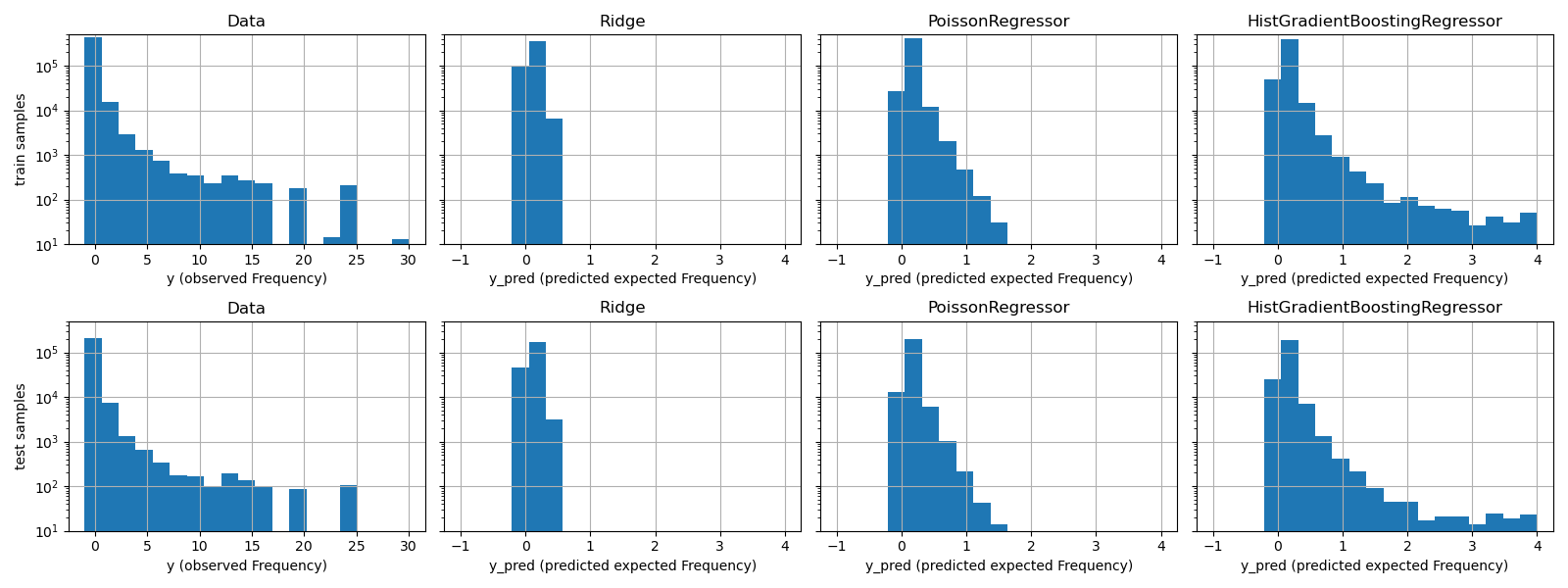

Evaluation of the calibration of predictions¶

To ensure that estimators yield reasonable predictions for different

policyholder types, we can bin test samples according to y_pred returned

by each model. Then for each bin, we compare the mean predicted y_pred,

with the mean observed target:

from sklearn.utils import gen_even_slices

def _mean_frequency_by_risk_group(y_true, y_pred, sample_weight=None,

n_bins=100):

"""Compare predictions and observations for bins ordered by y_pred.

We order the samples by ``y_pred`` and split it in bins.

In each bin the observed mean is compared with the predicted mean.

Parameters

----------

y_true: array-like of shape (n_samples,)

Ground truth (correct) target values.

y_pred: array-like of shape (n_samples,)

Estimated target values.

sample_weight : array-like of shape (n_samples,)

Sample weights.

n_bins: int

Number of bins to use.

Returns

-------

bin_centers: ndarray of shape (n_bins,)

bin centers

y_true_bin: ndarray of shape (n_bins,)

average y_pred for each bin

y_pred_bin: ndarray of shape (n_bins,)

average y_pred for each bin

"""

idx_sort = np.argsort(y_pred)

bin_centers = np.arange(0, 1, 1/n_bins) + 0.5/n_bins

y_pred_bin = np.zeros(n_bins)

y_true_bin = np.zeros(n_bins)

for n, sl in enumerate(gen_even_slices(len(y_true), n_bins)):

weights = sample_weight[idx_sort][sl]

y_pred_bin[n] = np.average(

y_pred[idx_sort][sl], weights=weights

)

y_true_bin[n] = np.average(

y_true[idx_sort][sl],

weights=weights

)

return bin_centers, y_true_bin, y_pred_bin

print(f"Actual number of claims: {df_test['ClaimNb'].sum()}")

fig, ax = plt.subplots(nrows=2, ncols=2, figsize=(12, 8))

plt.subplots_adjust(wspace=0.3)

for axi, model in zip(ax.ravel(), [ridge_glm, poisson_glm, poisson_gbrt,

dummy]):

y_pred = model.predict(df_test)

y_true = df_test["Frequency"].values

exposure = df_test["Exposure"].values

q, y_true_seg, y_pred_seg = _mean_frequency_by_risk_group(

y_true, y_pred, sample_weight=exposure, n_bins=10)

# Name of the model after the estimator used in the last step of the

# pipeline.

print(f"Predicted number of claims by {model[-1]}: "

f"{np.sum(y_pred * exposure):.1f}")

axi.plot(q, y_pred_seg, marker='x', linestyle="--", label="predictions")

axi.plot(q, y_true_seg, marker='o', linestyle="--", label="observations")

axi.set_xlim(0, 1.0)

axi.set_ylim(0, 0.5)

axi.set(

title=model[-1],

xlabel='Fraction of samples sorted by y_pred',

ylabel='Mean Frequency (y_pred)'

)

axi.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

Out:

Actual number of claims: 11935.0

Predicted number of claims by Ridge(alpha=1e-06): 10692.9

Predicted number of claims by PoissonRegressor(alpha=1e-12, max_iter=300): 11936.4

Predicted number of claims by HistGradientBoostingRegressor(loss='poisson', max_leaf_nodes=128): 12109.6

Predicted number of claims by DummyRegressor(): 11931.2

The dummy regression model predicts a constant frequency. This model does not attribute the same tied rank to all samples but is none-the-less globally well calibrated (to estimate the mean frequency of the entire population).

The Ridge regression model can predict very low expected frequencies that

do not match the data. It can therefore severly under-estimate the risk for

some policyholders.

PoissonRegressor and HistGradientBoostingRegressor show better

consistency between predicted and observed targets, especially for low

predicted target values.

The sum of all predictions also confirms the calibration issue of the

Ridge model: it under-estimates by more than 3% the total number of

claims in the test set while the other three models can approximately recover

the total number of claims of the test portfolio.

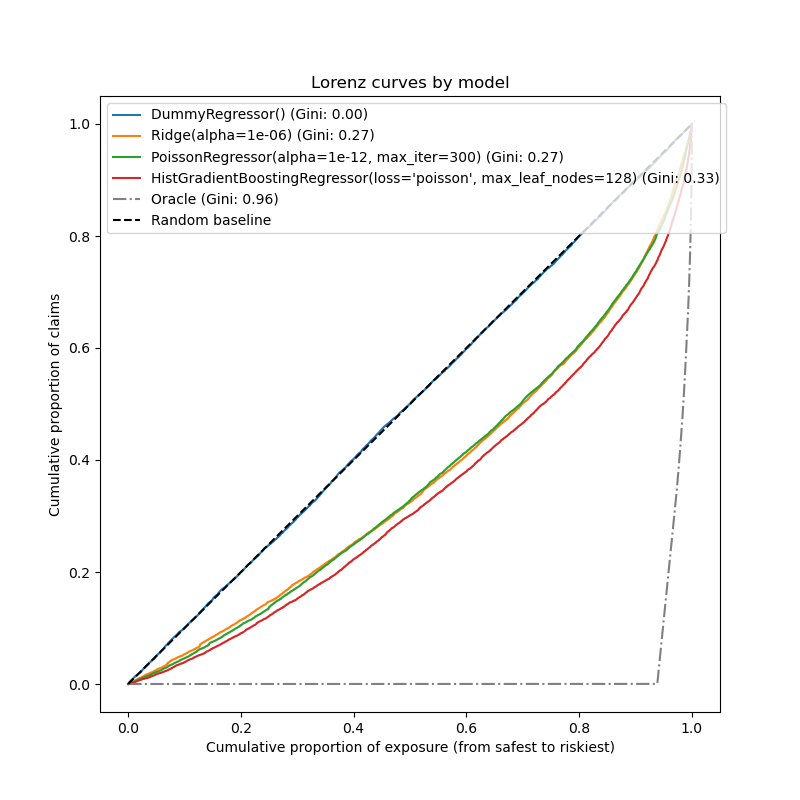

Evaluation of the ranking power¶

For some business applications, we are interested in the ability of the model to rank the riskiest from the safest policyholders, irrespective of the absolute value of the prediction. In this case, the model evaluation would cast the problem as a ranking problem rather than a regression problem.

To compare the 3 models from this perspective, one can plot the cumulative proportion of claims vs the cumulative proportion of exposure for the test samples order by the model predictions, from safest to riskiest according to each model.

This plot is called a Lorenz curve and can be summarized by the Gini index:

from sklearn.metrics import auc

def lorenz_curve(y_true, y_pred, exposure):

y_true, y_pred = np.asarray(y_true), np.asarray(y_pred)

exposure = np.asarray(exposure)

# order samples by increasing predicted risk:

ranking = np.argsort(y_pred)

ranked_frequencies = y_true[ranking]

ranked_exposure = exposure[ranking]

cumulated_claims = np.cumsum(ranked_frequencies * ranked_exposure)

cumulated_claims /= cumulated_claims[-1]

cumulated_exposure = np.cumsum(ranked_exposure)

cumulated_exposure /= cumulated_exposure[-1]

return cumulated_exposure, cumulated_claims

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 8))

for model in [dummy, ridge_glm, poisson_glm, poisson_gbrt]:

y_pred = model.predict(df_test)

cum_exposure, cum_claims = lorenz_curve(df_test["Frequency"], y_pred,

df_test["Exposure"])

gini = 1 - 2 * auc(cum_exposure, cum_claims)

label = "{} (Gini: {:.2f})".format(model[-1], gini)

ax.plot(cum_exposure, cum_claims, linestyle="-", label=label)

# Oracle model: y_pred == y_test

cum_exposure, cum_claims = lorenz_curve(df_test["Frequency"],

df_test["Frequency"],

df_test["Exposure"])

gini = 1 - 2 * auc(cum_exposure, cum_claims)

label = "Oracle (Gini: {:.2f})".format(gini)

ax.plot(cum_exposure, cum_claims, linestyle="-.", color="gray", label=label)

# Random Baseline

ax.plot([0, 1], [0, 1], linestyle="--", color="black",

label="Random baseline")

ax.set(

title="Lorenz curves by model",

xlabel='Cumulative proportion of exposure (from safest to riskiest)',

ylabel='Cumulative proportion of claims'

)

ax.legend(loc="upper left")

Out:

<matplotlib.legend.Legend object at 0x7efbfe0be2e0>

As expected, the dummy regressor is unable to correctly rank the samples and therefore performs the worst on this plot.

The tree-based model is significantly better at ranking policyholders by risk while the two linear models perform similarly.

All three models are significantly better than chance but also very far from making perfect predictions.

This last point is expected due to the nature of the problem: the occurrence of accidents is mostly dominated by circumstantial causes that are not captured in the columns of the dataset and can indeed be considered as purely random.

The linear models assume no interactions between the input variables which

likely causes under-fitting. Inserting a polynomial feature extractor

(PolynomialFeatures) indeed increases their

discrimative power by 2 points of Gini index. In particular it improves the

ability of the models to identify the top 5% riskiest profiles.

Main takeaways¶

The performance of the models can be evaluated by their ability to yield well-calibrated predictions and a good ranking.

The calibration of the model can be assessed by plotting the mean observed value vs the mean predicted value on groups of test samples binned by predicted risk.

The least squares loss (along with the implicit use of the identity link function) of the Ridge regression model seems to cause this model to be badly calibrated. In particular, it tends to underestimate the risk and can even predict invalid negative frequencies.

Using the Poisson loss with a log-link can correct these problems and lead to a well-calibrated linear model.

The Gini index reflects the ability of a model to rank predictions irrespective of their absolute values, and therefore only assess their ranking power.

Despite the improvement in calibration, the ranking power of both linear models are comparable and well below the ranking power of the Gradient Boosting Regression Trees.

The Poisson deviance computed as an evaluation metric reflects both the calibration and the ranking power of the model. It also makes a linear assumption on the ideal relationship between the expected value and the variance of the response variable. For the sake of conciseness we did not check whether this assumption holds.

Traditional regression metrics such as Mean Squared Error and Mean Absolute Error are hard to meaningfully interpret on count values with many zeros.

plt.show()

Total running time of the script: ( 1 minutes 3.386 seconds)